Jean Hélion

Selected Works

Jean Hélion

R...pour requiem, 1981

Acrylique sur toile

81x100 cm

Jean Hélion

Anémones d'hier et d'aujourd'hui, 1952

Huile sur toile

54 x 65 cm

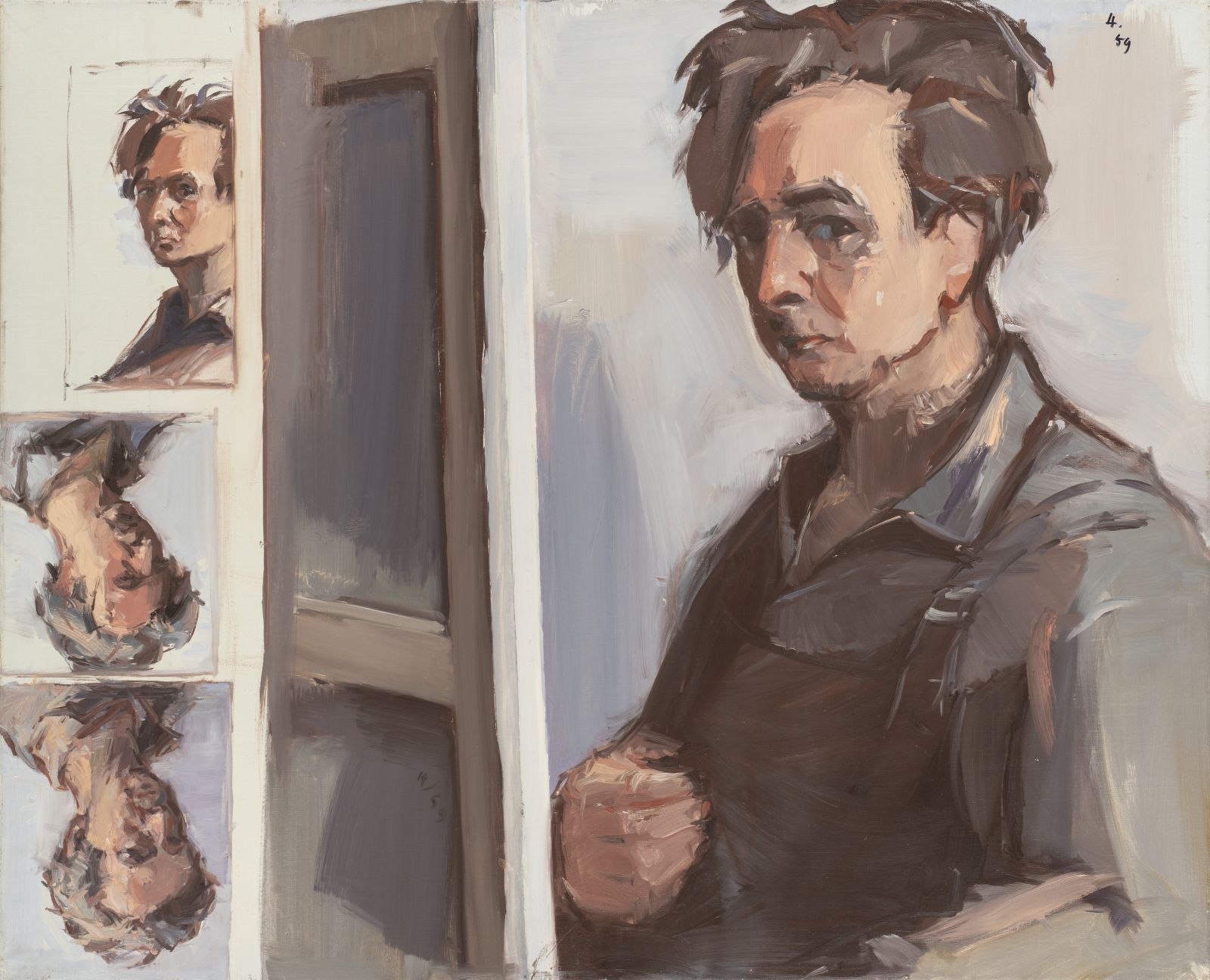

Jean Hélion

Planches autoportrait, 1959

Huile sur toile

81 x 100 cm

Jean Hélion

Suite pucière n°2, 1978

Huile sur toile

89 x 116 cm

Jean Hélion

Pantalonade, 1978

Acrylique sur toile

146 x 114 cm

Jean Hélion

Songe, 1962

Oil on canvas

Signed, dated and tilted on the back

Jean Hélion

Le barbant, 1957

Huile sur toile

81 x 100 cm

Jean Hélion

Abstraction, 1935

Lavis sur papier

23,5 x 32 cm

Signé et daté en bas à droite

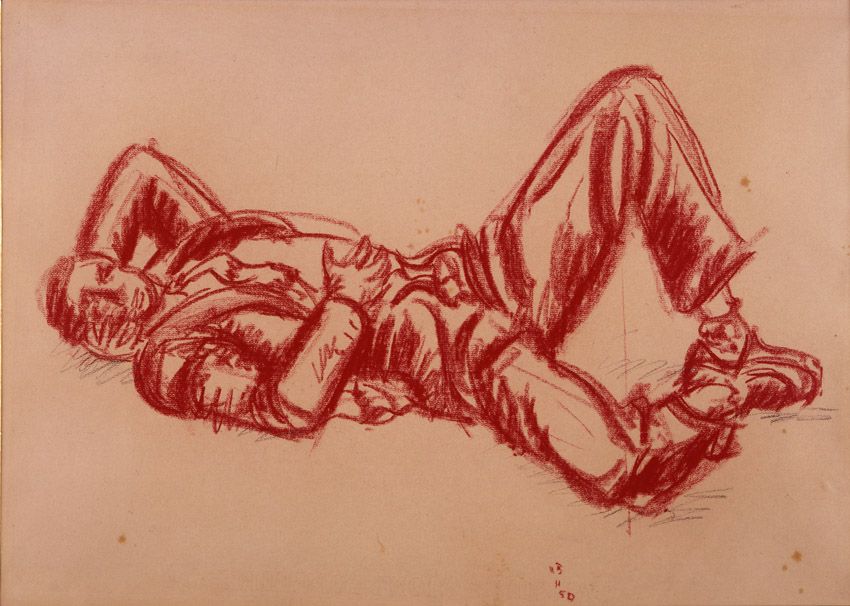

Jean Hélion

Le gisant, 1950

Craie rouge sur papier

42,5 x 59,5 cm

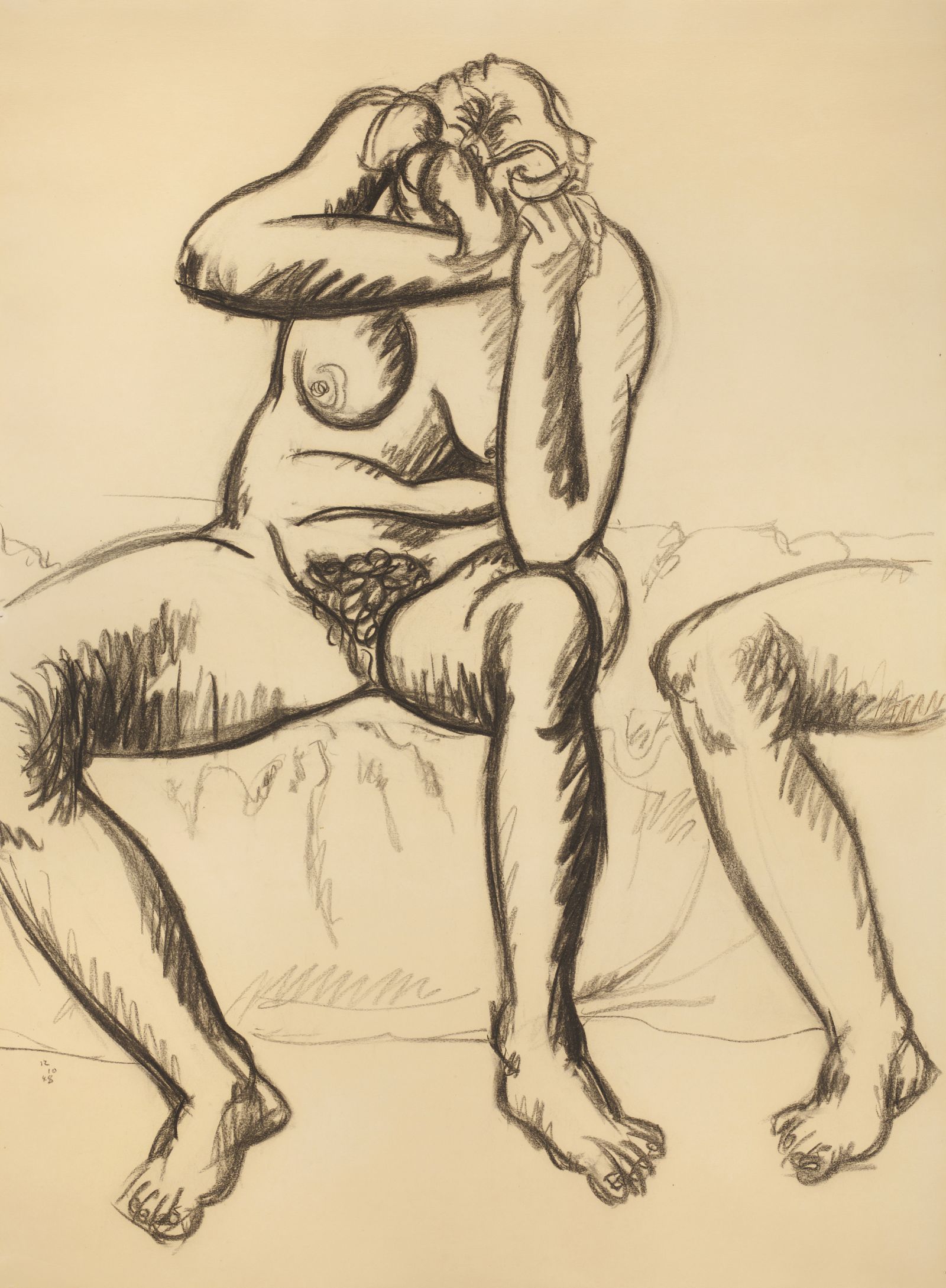

Jean Hélion

Nu accoudé, 1948

Fusain sur papier

99 x 74 cm

Some of the works depicted are no longer available.

Biography

Jean Hélion marks abstract painting then figurative. His painting becomes singular and acid, simplified and complex. At one time admired then misunderstood, abandoned by all and considered a renegade, Hélion immersed himself body and soul in figuration never to leave it and explore all its springs, writing his own language.